At the start of the 2024 season, the ECB decided to experiment with two types of cricket ball, Kookaburra and Duke’s, so that English cricketers could get used to the Kookaburra ball which is widely used around the world, as opposed to the Duke’s ball, which is only used in England, Ireland and West Indies. The experiment proved inconclusive, merely reinforcing the fact that good players will be able to cope with all situations, while the less able will struggle. A lot of runs were scored and not many wickets taken, so both Duke’s and Kookaburra balls got smashed regularly to the boundaries of all eighteen counties.

We should never forget the part that the county of Kent has played in the history of cricket ball manufacture. The first commercial enterprise to specialise in making cricket balls was established by a farmer, Timothy Duke, of Penshurst, who is credited with manufacturing the first ‘modern’ cricket ball as long ago as 1760. It seems very unlikely that Duke was able to make a living out of making cricket balls at that time, but it was no doubt a useful sideline to being a farmer. Even then, the game was very much connected with both the aristocracy and gambling, so there was plenty of money in the game, and no doubt the Duke family enjoyed good margins. Their cricket ball business flourished and in 1775 received a royal warrant as manufacturer of cricket balls to the then Prince of Wales, later King George IV, who loved to gamble, and who was often to be seen on the boundary at the great games of the day.

Duke’s continued to grow, and in 1920 was acquired by John Wisden and Co., and subsequently by Gray Nicholls. In 1987, under the name British Cricket Balls Ltd, it was bought by an Indian businessman, Dilip Jajodia. It remains the leading British based manufacturer of cricket balls, although it has long left Penshurst and is now rather more boringly based in Walthamstow.

For many years, Duke’s had a very strong Kentish rival from a tiny village by the Medway. Teston, pronounced Tee-s(t)on, is a small village just south of Maidstone, famed mainly for its Grade 1 listed mediaeval bridge across the River Medway, which dates from the 14th or 15th century. In the 2011 census the population of Teston was just 637, but that has not prevented the village from fielding a cricket team, which has played at the big house, Barham Court, since the end of the 19th century. Over the years they have met with mixed success.

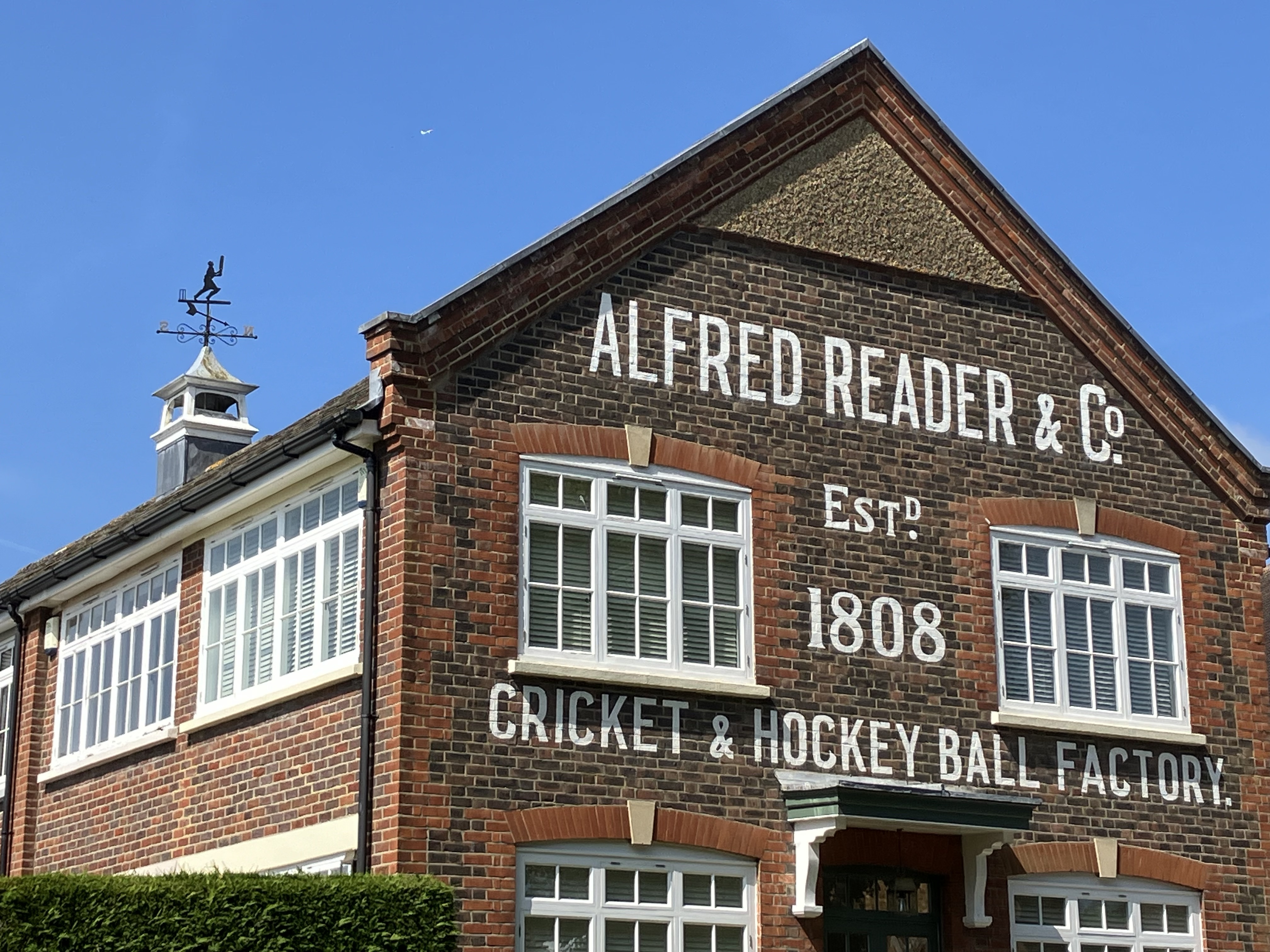

However, the village’s main connection with cricket is not its on-field performances over the years, but Alfred Reader and Co., who for over two centuries have been involved in manufacturing cricket balls. As you travel along the A26 from Maidstone to Tonbridge, turn right just past Barham Court, onto the Malling Road. Within a couple of hundred yards you will pass a building with the words “Alfred Reader and Co. Estd. 1808 Cricket and Hockey Ball Factory” painted in large white letters on its outside. Clearly there is no factory there now, merely those words written on the side of what is now a private dwelling, fronting a small close with a dozen houses, called Readers Court. (As an aside, please feel free to be disgusted by the lack of an apostrophe in ‘Readers’. That stems from grammatical incompetence on behalf of Maidstone Borough Council).

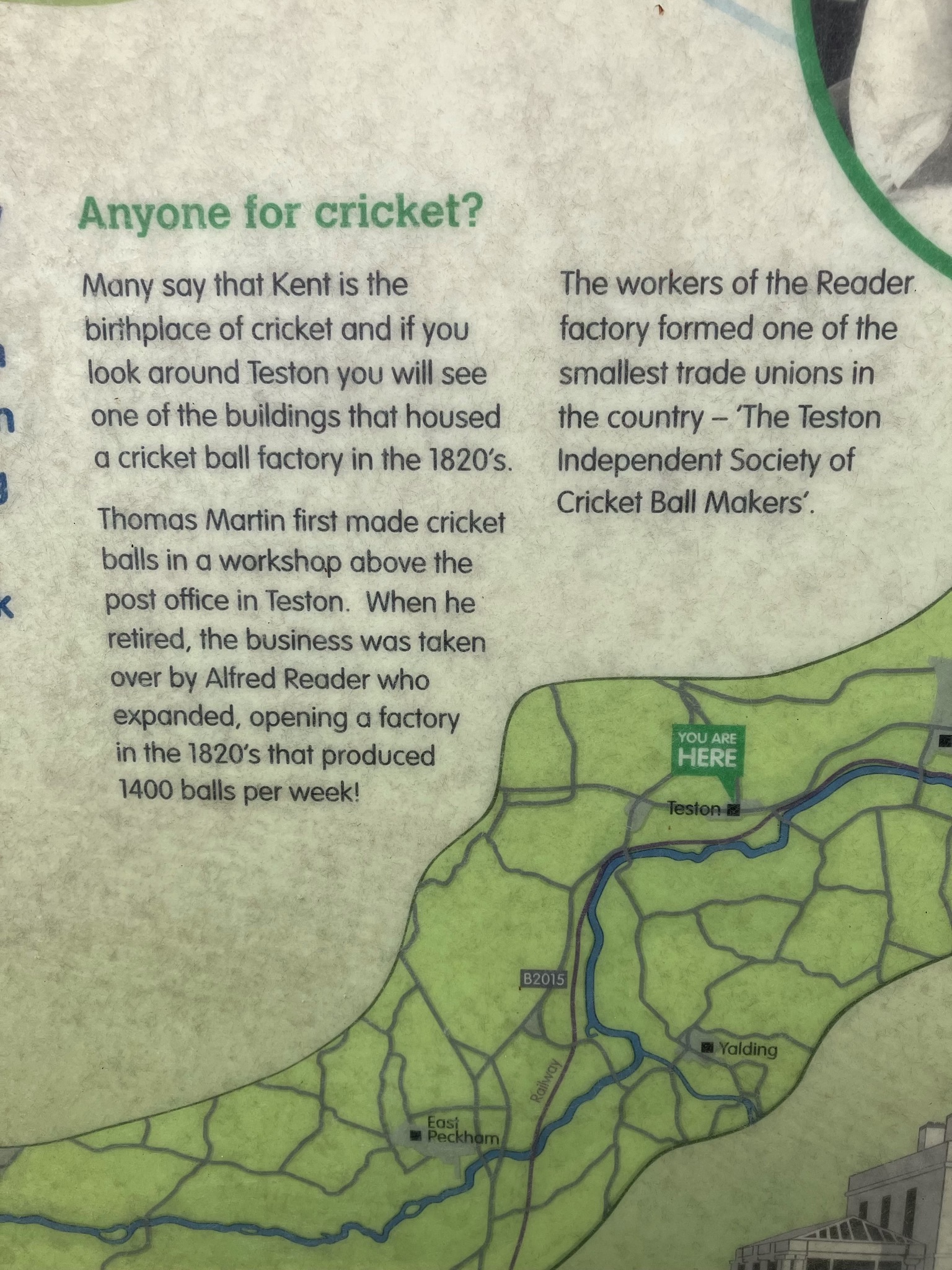

A few hundred yards away, between the village shop and the church, there is a tourist information sign that explains that a certain Thomas Martin made cricket balls in a factory above the village post office from the 1820s. So why do the big white letters say the factory was established in 1808? 1808 was a time when England was preoccupied with the possibility of invasion by Napoleon’s army, and very little organised cricket was played. It seems to have been an even less auspicious time to start making cricket balls than when Duke’s began half a century earlier, and when Duke’s began, they had no local rivals. Indeed, Lord Harris’s seminal History of Kent Cricket contains details of no matches played in the county that year. Why set up a factory making balls for a game very few people were playing? What’s more, the first hockey club in England was not established until about 40 years later, and although there were games similar to what we now call hockey at that time, it seems very unlikely that anybody could make a living from making balls for such an obscure pastime. My guess is that Thomas Martin had previously worked for Duke’s and felt he could do better.

Trade was clearly good enough for Thomas Martin and his family to keep out of the workhouse, and around 1820, he retired from an active role in the factory. He handed it over to Alfred Reader, who, it is said, employed a large percentage of the village population and soon increased production up to 1400 balls a week. By the time that cricket, and to a lesser extent hockey, were flourishing again in the mid-1800s, Reader’s cricket balls were very widely used, and no doubt business was good. There is some doubt about exactly when Mr Reader took over the business, as a newspaper interview with a later generation Alfred Reader in 1939 states that early owners of the business included Fuller Pilch, but certainly by the time organised county cricket was getting under way in the 1860s and 1870s, Reader’s was the name on their cricket balls.

Throughout the Victorian era, Duke’s and Reader’s flourished as cricket grew rapidly to become the elite national game. Whether the conditions for the workers were particularly pleasant is another matter. The Teston workers formed a trade union in 1919, The Teston Independent Society of Cricket Ball Makers, which was only disbanded in 2006, and which for many years was the smallest trade union in Britain, with fewer than 50 members. In 1962, as cricket balls from Pakistan were undercutting Reader’s prices, the workers threatened to go on strike for an increase in their 4/- (20p) an hour pay, and even Leslie Ames, then Secretary of Kent CCC, was brought into the discussion. He suggested that “the craftsmen are killing the goose that lays the golden egg” by asking for such high wages. From the mid-70s onwards, there are regular stories of commercial difficulties and industrial disputes in the local press. The writing was on the wall.

The Reader’s factory building that still stands in Teston was built in 1927, and until the last couple of decades of the last century, regular advertisements were placed in the newspapers by Reader’s looking to employ young people in their factory. However, in 2000, the factory was closed and Reader’s became part of the Kookaburra empire in 2002. They still have a small presence in Mereworth (pronounced Merry-worth – very few Kent villages are pronounced the way they are spelt), a village about 3 miles to the west of Teston, and the name lives on as a brand. Reader’s balls are still widely used in UK, but no longer made in Kent.

So the two giants of cricket ball manufacture in Kent still exist, and without their skills and manufacturing know-how in the early days of cricket, who knows how the game might have developed?

0 Comments