This is the story of a remarkable man, captain of Kent for a season, but a national war hero for all seasons. His name was John Evans, and he was born on 1 May 1889 at Highclere in Hampshire, close to Newbury where one year earlier his father had founded Horris Hill preparatory school. Evans senior was a fine sportsman, having played first class cricket for Oxford University, captaining the side in 1881. In 1882 he began his teaching career at Winchester College, and apart from a handful of games for Hampshire and Somerset, retired from first class cricket and devoted himself to teaching. In 1888 he left Winchester to set up Horris Hill preparatory school, and it was there that his son Alfred John Evans, was born.

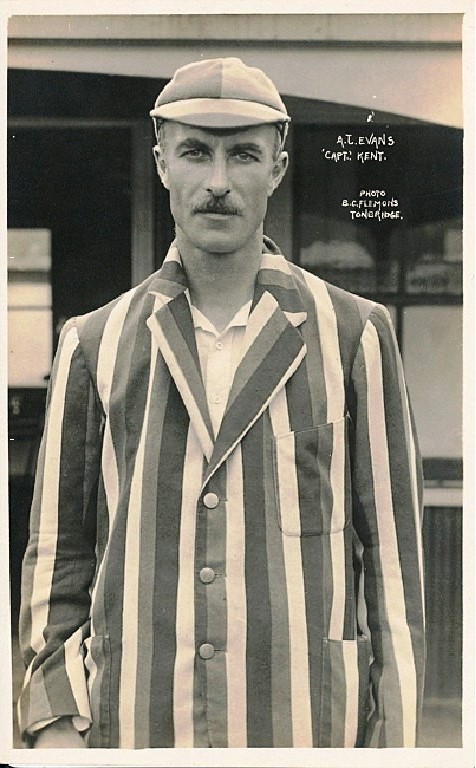

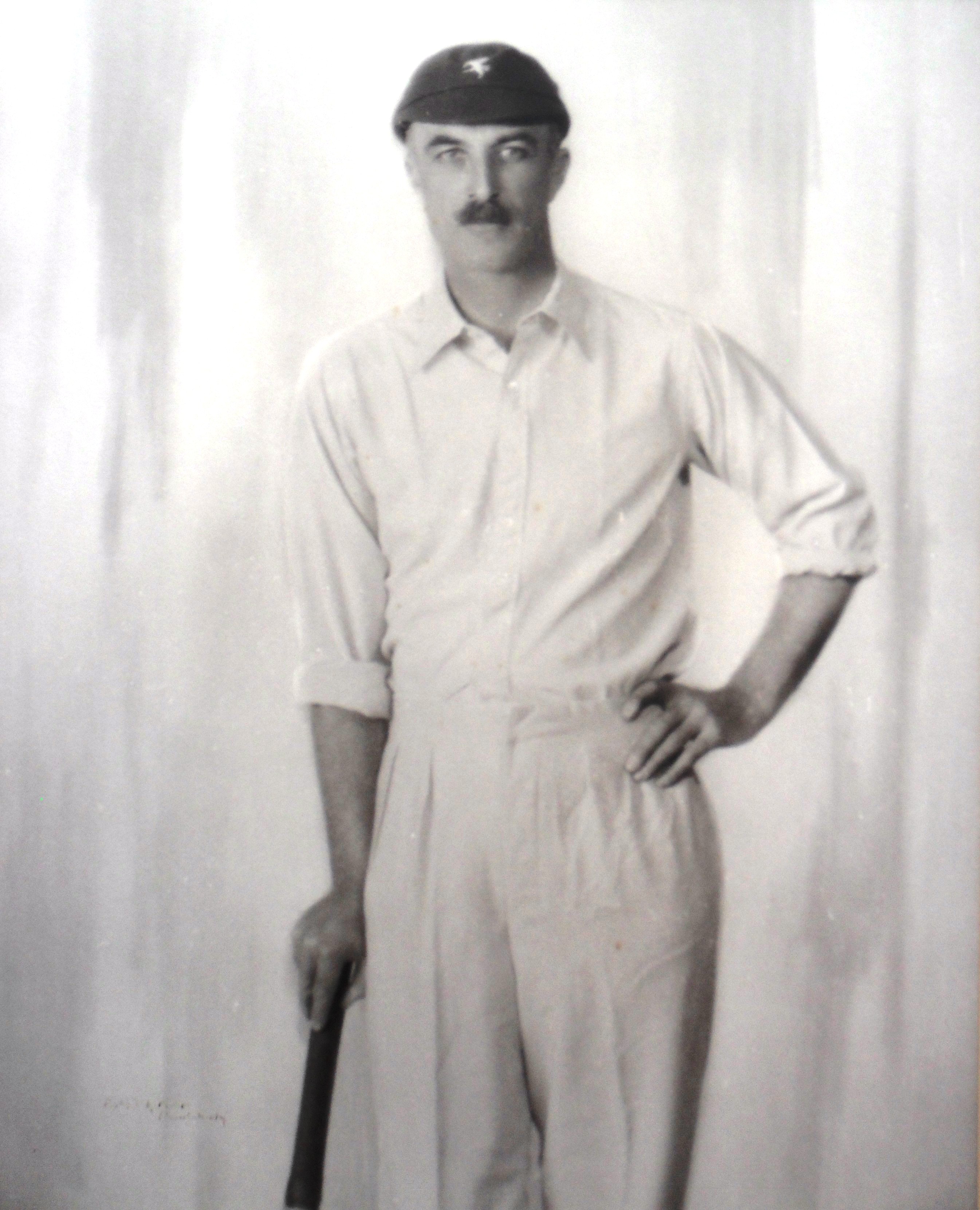

Johnny Evans inherited all of his father’s athletic skills and then a bit more. Having done his stint as a prep schoolboy under his father’s rule at Horris Hill, he moved up to Winchester College, where he was in the cricket XI for three years. The next step was Oxford, where he won Blues from 1909 to 1912, and, emulating his father, was captain in 1910. He also represented the university at rackets and golf, and first played county cricket, for Hampshire, in 1908.

On graduating from Oxford, Evans followed in his Dad’s footsteps once again, and joined the teaching staff at Eton College. He then spent a year in Germany, paid for by Eton, becoming fluent in German. However, he gave up teaching after another year or so, on discovering that he “hated small boys” (a good enough reason in my book), and at last he did something his father had not done. In 1914, Archduke Franz Ferdinand was assassinated, the Hapsburg empire began to crumble and the Great War broke out. Johnny Evans, gentleman and fluent German speaker, had already been noticed by the War Office as a suitable candidate to join the newly formed Intelligence Corps, and in August 1914, he was sent to France as part of the corps.

His role was as an observer for the Royal Flying Corps, a job that involved leaning out of flimsy aircraft flying at about 250 metres above the ground over enemy lines, taking photographs under fire – not a recipe for a long life. On 16 July 1916, his aeroplane was forced to make a landing behind enemy lines, and he was captured, and imprisoned at Clausthal, south of Hanover in Lower Saxony. He soon escaped and almost made it to the Dutch border, around 300 miles away, but was recaptured and sent to Ingolstadt, on the Danube, where the POWs were housed in old forts. He made several escapes, but was recaptured each time, until the day when a number of English prisoners, including Evans, were transferred to another camp. This time, he had more luck. He and another prisoner jumped from the moving train and began walking to the Swiss border, a long way away. The trek took them 18 days, but eventually on 9 June 1917 they reached the safety of Switzerland. The indefatigable Evans quickly got himself back into the war, but because escaped POWs were not allowed to return to the same theatre of war, he was posted to the Middle East, firstly to Egypt at the end of 1917, and then to Palestine early the next year, where he was put in command of a bomber squadron. In March that year, he was captured again when a blocked fuel pipe forced him to land in enemy territory. In no time they were captured by Arabs, and then, as he later described it, “soon afterwards rescued!!! By Turks.”

The complicated loyalties in that part of the world so late in the war meant that Evans and his fellow prisoners never felt secure, whoever was guarding them, and of course Evans tried to escape many more times. His final effort came when he heard that sick officers were to be taken by train to Smyrna to be exchanged for sick prisoners from the other side, and he bribed a doctor to get him onto the train. Once in Smyrna, he thought about surrendering once again to the Turks, so that he could then work out how to escape ‘legitimately’, to use his word, but as he could see the war was so near to an end, he took the less foolhardy route and boarded the ship. He arrived in Alexandria, and safety, in November 1918.

For all his escaping efforts, he was awarded a bar to the Military Cross he had won earlier in the war. Once back in England, he wrote about his experiences as a prisoner of war in his book, The Escaping Club, which became a best-seller. As if writing a book was not time consuming enough, he got married in October 1919, and in 1920 he made his last appearance for Hampshire, against Kent, at Canterbury. Hampshire were well beaten, but Evans scored more runs in the match than any of his Hampshire team-mates. Early in 1921, when English cricket was definitely in the doldrums, he had been picked to play for MCC against the visiting Australians, and his 69 not out certainly impressed the England selectors. Having now qualified by residence for Kent, a week later he made his debut for the county, and promptly scored 102 against Northamptonshire. This was enough for the England selectors, who were smarting from defeat in the First Test by ten wickets They picked Evans, along with three other debutants, for the Second Test at Lord’s. Things went slightly better for England, in that they only lost by eight wickets, but Johnny Evans scored only 4 and 14, the rumour being that he was unnerved by the occasion and the speed of Ted McDonald, the great Australian opening bowler. For a man who had shown such bravery and nerve in wartime, that seems an unlikely excuse. More likely, he wasn’t quite good enough. He, along with two of the other three England debutants in that game, Alfred Dipper of Gloucestershire and Jack Durston of Middlesex, never played for their country again.

After that summer, Evans put his business life ahead of his cricket, and played only sporadically for Kent. Then in 1927, much to the surprise of many, the 38 year old Evans was offered the county captaincy, and he accepted. For the first half of the season, he played very well, hitting three centuries and several fifties, including 143 (his highest score) against a Lancashire attack which included the fearsome Ted McDonald. His batting fell away during the latter part of the season, no doubt affected by the strains of a full season of cricket after years of sitting behind a desk, and by the end of the summer, in which he hit 832 runs at an average of 25, he announced he was stepping down from the captaincy. Kent had done fairly well under his leadership, finishing 4th, just one place below their 1927 finish, but he was happy to hand on the position to Geoffrey Legge. In 1928, he played eight championship matches for Kent, but finished his first-class career at Eastbourne, playing for Harlequins CC against the touring West Indians, at the end of August that year. Harlequins made 676 for 8 declared, with Evans making 124 out of a 7th wicket partnership of 255 with another Kent man, C.H. ‘John’ Knott who made 261 not out. The Harlequins won by an innings, a good way for John Evans to leave the game.

He did not leave the escaping game, though. When the Second World War came along, he was 50 years old, but was seconded to MI9 to help plan escape routes from occupied Europe for POWs and others stranded behind enemy lines. He went with the invading armies into Europe in July 1944, shortly after the D-Day landings, and helped to find more POWs and facilitate their release and journey home.

He died in September 1960, aged 71, having led a rather more interesting life than most who have captained, or even played for, Kent CCC.

0 Comments