This is the story of Kent’s first cricketing import. Of course, when this particular player moved to Kent from ‘abroad’, there was no Kent County Cricket Club – that was almost a century in the future – and he was also not, in the modern sense of the word, a foreigner. He did not come from ‘abroad’, he came from Hampshire. However, in the eighteenth century, a foreigner was anybody who came from a distant part of the country, and what we would now call a foreigner, i.e. a person from another country, would have been known as a ‘stranger’.

As Derek Carlaw has noted in his remarkable A to Z of Kent Cricketers, “Kent have a long and for the most part honourable tradition of importing players but by the standards of the day even Steve Waugh was hardly more eminent than James Aylward when Sir Horace Mann lured him from Hambledon in the late summer of 1779.” James Aylward was born in 1741, the son of a farmer, and played his first game for the great Hambledon club in 1773. He quickly became established as a dour, defensive and almost impossible to remove left-handed opening batsman, more of a Boycott than a Sehwag. In 1777, he had his greatest match, playing for Hambledon against ‘England’, at Sevenoaks Vine. He hit the almost unimaginable score (in those days) of 167, and according to Scores & Biographies he came in to bat at 5 p.m. on Wednesday 18th June, and was not dismissed until 3 p.m. on Friday 20th. Of course, we do not know the hours of play, and it was virtually on midsummer’s day when the evenings would have been very light, but it seems likely he must have batted for a good twelve hours or so in compiling this mammoth score.

One man who was almost certainly watching the match at Sevenoaks was Sir Horace Mann, the cricket and gambling lover who owned a large property at Bishopsbourne, near Canterbury. It would have been a grand social occasion, a regular fixture which had been played for several seasons, with, in this game, the Duke of Dorset playing for England and the Earl of Tankerville playing for Hambledon (who were advertised as ‘Hampshire’ but rarely included anybody who was not a Hambledon regular). Sir Horace would not have missed the chance to watch his favourite sport, and to gamble heavily on it, and he must surely have thought that if he had this Aylward fellow playing for his team on a regular basis, he would win more games, and bets, than he would lose. Aylward’s team, incidentally, scored 403 all out in response to England’s first innings total of 166, and bowled them out in their second innings for just 69, to give Hambledon the win by an innings and 168 runs, the biggest margin of victory ever recorded by Hambledon. Aylward’s 167 was not the first ever century, but it was the highest score made in an important match to that time, and was not beaten until 1820. What’s more, it was one of the first major games played after the third stump was introduced, which was meant to help bowlers and which makes his effort all the more remarkable.

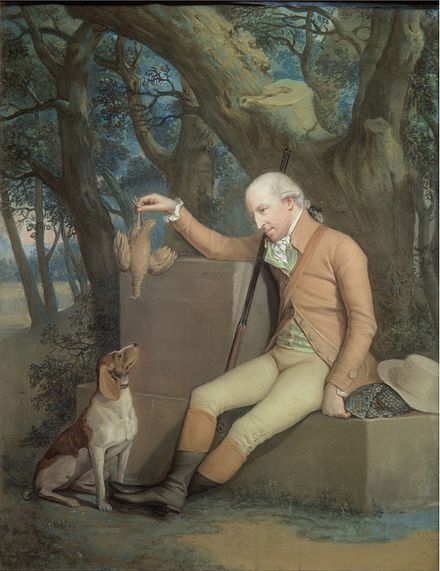

Aylward is described by Richard Nyren in his book Cricketers Of My Time as ‘a stout, well-made man, standing about five feet nine inches, not very light about the limbs’. Despite the fact that Aylward deserted his beloved Hambledon, Nyren goes on to describe him as ‘one of the safest hitters I have ever known in the club’ but ‘not a good fieldsman’. Put him at second slip then, and hope he doesn’t have to chase any balls down to third man.

Poaching cricketers was not unknown in eighteenth century cricket, but in order to persuade a player to move his home and his family to another part of the country, there had to be more than just the promise of a few games of cricket. Sir Horace accordingly offered Aylward the position of bailiff at Bourne Park. There is no evidence that Aylward had any previous experience as a bailiff, or that he was much good at the job once he had moved to Kent, but he carried on playing for a variety of teams in the county until at least the mid-1790s, by which time he was well into his fifties. Sir Horace’s decision to recruit Aylward seemed to pay off almost immediately, as in his first big match of 1780, a few months after his move to Kent, Aylward helped Sir Horace’s XI to a seven wicket victory against the Duke of Dorset’s XI, again at Sevenoaks Vine, by scoring 47 in the first innings, and 12 not out in the second innings, being at the crease when the winning runs were hit. He also, for a reputedly poor fielder, nevertheless took three catches in each innings of the Duke’s XI, thereby no doubt earning his bailiff’s salary for the year.

According to Cricket Archive, Aylward scored 3869 runs in 107 major matches, at an average of 19.24, including over 1,000 each for Hampshire/Hambledon and for Kent, not to mention another 350 or so for other Kent teams. 604 of these runs were against Hambledon, the team he had been tempted away from. At Bishopsbourne in 1786, Sir Horace arranged a match between VI of Kent and VI of Hampshire, and appointed himself captain. Somewhat eccentrically, Mann asked his professional opening batsman to bat last, and Aylward came to the wicket when only two runs were needed for victory, but the Hampshire Six needed only one wicket. Aylward had his slice of luck, being dropped before he had scored, but eventually, after a reported 94 balls, Aylward got the final two runs for victory.

It is said that Aylward was not a success as Mann’s bailiff, but given the mercurial character of Sir Horace himself, it cannot have been an easy task. After about five years, we find Aylward as the licensee of the White Horse at Bridge (a pub which still stands but which has been closed since last October, I understand) where he stayed for ten years or so, offering ‘a good ordinary at one o’clock’, ‘a booth and good accommodation’, as well as catering for matches in Bourne Paddock.

Between his arrival in Kent in 1779 and 1792, he fathered eight children, one of whom was named Horace James after the two most influential men in Kent cricket at the time, Sir Horace and himself. In the mid-1790s, around the time that Hambledon’s fortunes waned and the centre of power in cricket moved to London, he too moved to the capital, and played a few games for London teams. His last known game was for XXII of Middlesex against XXII of Surrey in 1802, when he was 61 years old. He lived on until 1827 and is buried, with no tombstone, in St John’s Wood Church, right next door to Lord’s.

0 Comments