I recently spent some time with a dozen of the young players of the Kent Academy. I was not, fortunately, being bowled at in the nets, nor even tossing up a few gentle leg breaks to bolster their confidence as batsmen. We were talking about the heritage of the club, and how they might hope one day to write their names in the record books as firmly as Woolley, Blythe, Ames, Wright, Cowdrey and Underwood, to name just a few.

I was surprised how aware they were of the history of the game, even though the cricket they are learning today is quite different from the game that was played in those Kentish greats’ heyday. Cricket has clearly changed as much over the past twenty years as it has at any time since overarm bowling was legalised. The 1960s brought in the abolition of the distinction between amateurs and professionals, and the beginnings of limited over cricket. Those innovations in turn brought in new styles of batting and bowling, new equipment, new levels of fitness. But it also brought with it, in the sixties and seventies, a sense of caution among those whose livelihood depended on their batting and bowling averages, with the result that cricket found itself unable to match other sports as popular entertainment. Cricket was in danger of becoming terminally dull.

The Packer revolution – which was all about television rights, not helping underpaid players – in the 1970s began the transformation of cricket into a game watched from an armchair at home rather than from a bench at a bleak and unfriendly county ground, but even Packer did not change the basics of the way the game was played. It was not until the 21st century and the onset of T20 that cricketers began to see that the safest way to make big money was to take big risks. Television rights for T20 around the world have revolutionised players’ bank balances, and several cricketers are starting to realise that first-class and Test match cricket is not the best way to make your millions, nor indeed to become heroes (and heroines) to the youth of today. No doubt some of the young people I was talking to the other day will see T20 as their obvious career path, and who could blame them?

It seems ironic that the popularity of T20 around the world began when India, who had previously all but ignored the format, won the inaugural ICC T20 World Cup in 2007. Its subsequent growth on the sub-continent was undoubtedly spurred on by the vast amount of money bet on each game – exactly the way the game of cricket had originally grown in the eighteenth century, when rich patrons gambled huge sums on the outcome of matches, and were not afraid to try to fix the odds in their favour. In Kent we had one of the great patrons and gamblers of the game, Sir Horatio Mann.

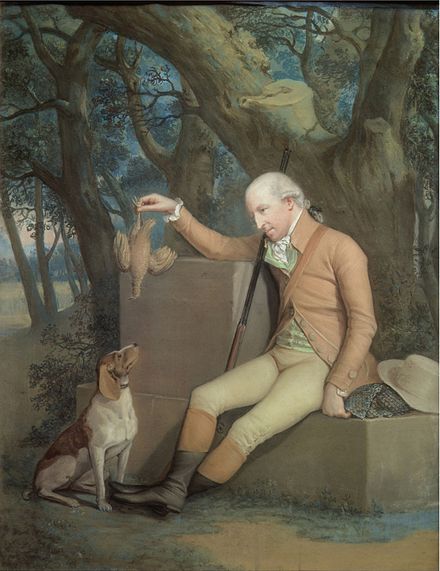

Sir Horatio Mann and his hound

Sir Horatio Mann (1744 – 1814) was a landowner with properties at Linton and Boughton Malherbe, and subsequently with a main residence at Bishopsbourne, near Canterbury, where he created a cricket field, Bourne Paddock, which staged many great matches. He played regularly until his election as MP for Sandwich in 1774, and was described as ‘a batsman of great might’. Perhaps he was the Chris Gayle or Brendon McCullum of his day, with a batting style more suited to T20 than Test cricket.

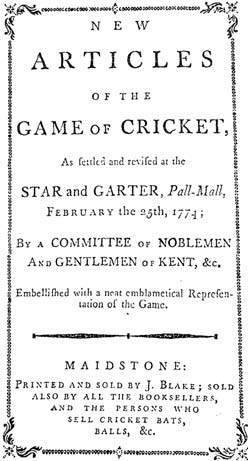

Gambling was his main passion in life, and cricket the vehicle for his passion. In this he was very similar to two of his contemporaries whose names are linked with the Hambledon Club, Rev. Charles Powlett and Philip Dehany. All three men were wealthy, aimless and probably rather bored, despite Mann and Dehany both being Members of Parliament for a time, and Powlett being the eldest son of a duke, albeit on the wrong side of the blanket. All three were part of the “Committee of Noblemen and Gentlemen of Kent &c.” who convened at the Star and Garter Inn in Pall Mall on 25th February 1774 to draw up a revised set of Laws for cricket. The nitty-gritty of the 1774 code is to be found in the final law, which concerned the governance of bets on the game. Here we see the hands of Sir Horatio, Powlett and Dehany at work.

“Bets.—If the notches of one player are laid against another, the bet depends on both innings, unless otherwise specified.

If one party beats the other in one innings, the notches in the first innings shall determine the bet.

But if the other party goes in a second time, then the bet must be determined by the number on the score.”

The Laws were published in Maidstone, no doubt with the assistance of Sir Horatio, so that all England should know how to bet properly on each game. Mann himself, however, was such a poor gambler (unlike Powlett and Dehany who prospered despite – or perhaps because of – never being above a little cheating here and there) and died a poor man. His nephew and heir, James Cornwallis, inherited the estate of a man described as “really ruined.” “The sums Sir Horatio expended are beyond all belief, or rather squandered,” his brother-in-law was recorded as saying.

I would certainly not go so far as to suggest that the ECB are at risk of squandering sums beyond all belief with the new T20 competition due to start in 2020, because the market for “people who do not yet know they like cricket” obviously has enormous potential. T20 has one very major advantage over the first-class game in reaching out to the wider public – it very closely resembles the game that thousands of village and club sides play every weekend, and at the end of the working day. I’ve played T20 cricket for the village on many a long summer evening, years before the term was ever invented. Cricket at this social level is a single innings, limited overs affair, in which big hitting, tight bowling and attempts at athletic fielding are equally important. So is T20. But cricket at first-class level is a completely different kettle of fish, and very few people have had the experience of actually playing this sort of cricket.

Any pub footballer will have played 90 minutes with exactly the same rules and dimensions as those which Ronaldo, Messi and Rooney have always played to, and any public park tennis player will have played exactly the same game that Roger Federer and Serena Williams play. Of course the skill levels may not be quite as high, but the rules, the playing area and the scoring system are the same. This applies to pretty well any sport you can think of. Cricket is the exception, or it was until T20 was invented for professional cricketers to play. That is one of the reasons it has taken such a rapid hold on the sporting public’s imagination, and therefore why it is so popular with the gambling community. When those gentlemen and noblemen at the Star and Garter in 1774 were working out the Laws of cricket, they were discussing a game that they all played, a game of one afternoon’s duration, on which bets could and would be made. It has taken the best part of 250 years for cricket to come full circle. The inheritors of Sir Horatio Mann’s obsession are thriving, or at least the bookmakers are.

Should we in Kent be proud of Sir Horatio for his love of cricket, or should we condemn him for his love of gambling? The one could not live without the other then, and it seems they cannot do so now. As guardians of the heritage of the game of cricket, especially in Kent, one of its birthplaces, we must fear for the future of county and Test cricket as the juggernaut of T20 rolls on, but those Academy students have an exciting range of options ahead of them. Will they stick with the red ball, and be among the saviours of long form cricket? I wouldn’t bet on it.

0 Comments