Birthdays are a mixed blessing. One a year is probably enough, but they are fun when they happen, even though at my age I realise I’ve had most of them already. I’ve long dispensed with party balloons, Pass The Parcel and Musical Chairs, but I’m still partial to a bit of lemon drizzle cake with a candle on top, and I’m certainly not yet ready to forgo the pleasure of receiving a present or two.

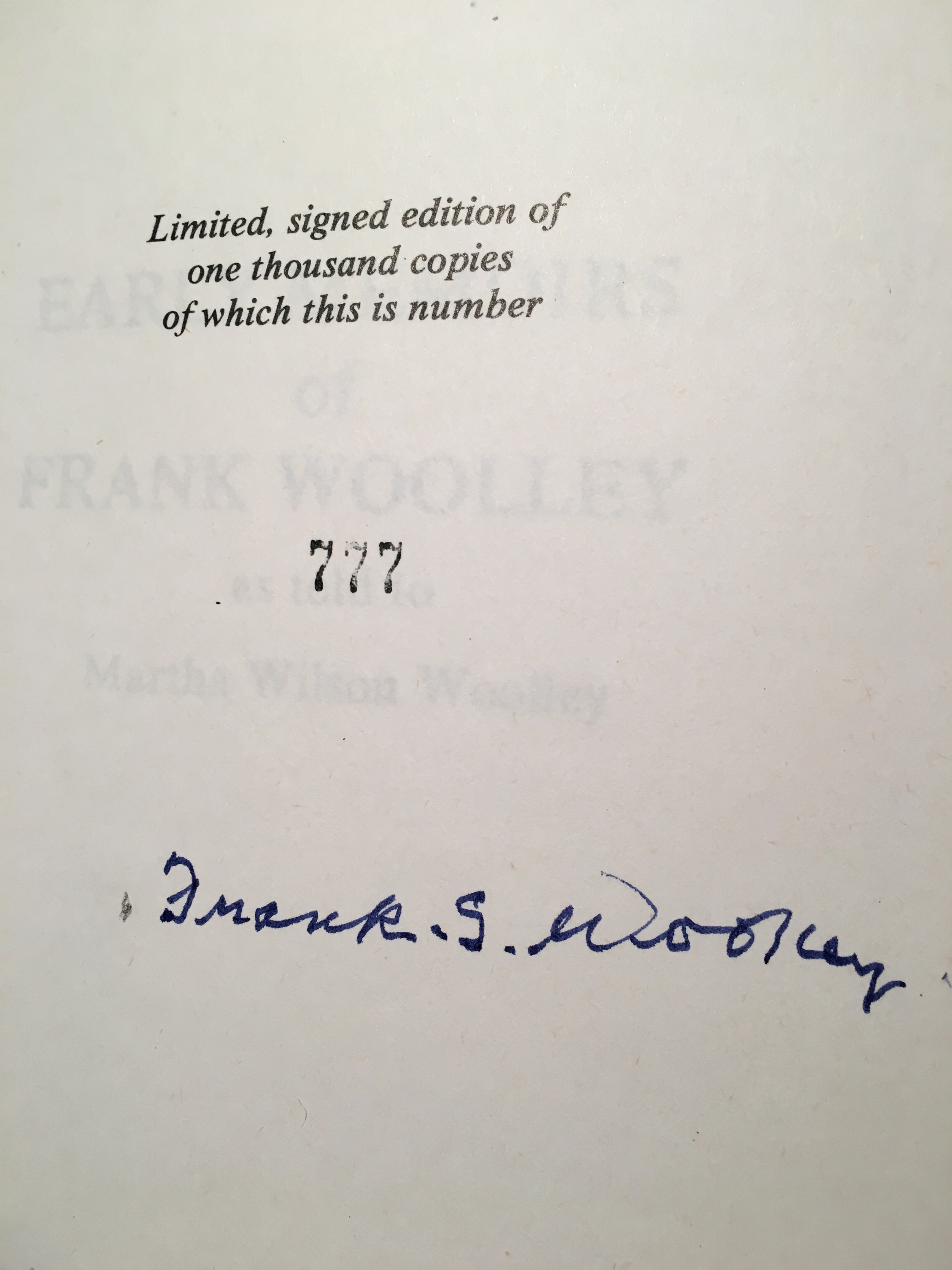

My birthday this year fell in February, as it does, by a remarkable coincidence, every year. I won’t bore you by listing all the cards and presents I received this year (although the list seems to get shorter every year), but I will mention one present that was particularly good to receive. It was a short book, published in 1976 by The Cricketer in a limited edition of 1,000 copies, entitled Early Memories of Frank Woolley, as told to Martha Wilson Woolley. Only 52 pages, maybe, but full of interesting and quirky facts, and including the then 89-year-old’s signature in blue-black Parker Quink.

Woolley’s early memories, “the recollection of my childhood in Tonbridge, from the day I was born until I joined the staff of Kent County Cricket Club at the age of fourteen” show that although much in the outside world has changed, “Humanity has not altered. The terrorists of today bear a striking resemblance to those who plagued us in 1887.” Today for Woolley was 1976, but almost half a century later, humanity is still living down to its reputation.

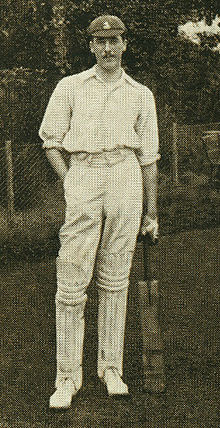

Frank Edward Woolley was the fourth son of Charles and Louise Woolley, proprietors of Woolley’s Cycle and Engine Works, 72 High Street, Tonbridge. Frank was born on 27 May 1887, with club feet. It is not clear exactly what the doctors meant by club feet 135 years ago, but his condition “caused much concern until I had proved I could walk and run even better than my brothers.”

Nevertheless, Frank himself was not aware of his deformity until he began to play football for Tonbridge and had to have boots made that would fit. It is interesting that two of the greatest Kent cricketers of all time had foot problems. Colin Cowdrey’s flat feet got him out of National Service, and nobody would ever have called him the fastest man over 22 yards, but he scored a mountain of runs all the same.

Woolley also had special hands. Like one of his elder brothers, Fred, Frank was left-handed “and remained left-handed throughout life.” That may sound like an obvious statement, but in his childhood days many naturally left-handed children was forced to learn to write with their right hands. Luckily Woolley escaped this fate, although even if he had learnt to write right-handed, he would undoubtedly still have played cricket left-handed. Such was his skill and success as a left-hander, “that certain noted doctors, puzzled by my intricate spinning, made me promise to leave the hand for medical history. I regret that I have been unable to oblige them on this matter, for I have outlived them all.” Not that Frank considered his hand was anything particularly special: in a brief footnote, he observed that “there are as many ways of spinning a ball as there are men who spin.”

Frank’s brother Fred, incidentally, would have been, in Frank’s estimation, “one of the greatest left-handers in England”, but he suffered an injury playing football, which ended his hopes of a sporting career. As an aside, it is worth noting again that the five most prolific bowlers in Kent’s history – Freeman, Blythe, Underwood, Wright and Woolley – all had a standard delivery that turned the ball away from the right-handed batter. Three were left-handed and two were leg break bowlers. Why should that be?

Frank’s childhood was, in his mind, idyllic. “Fortunately my parents were not rich, and I was therefore spared the inconvenience of being uprooted at intervals and trundled away to a Riviera in search of sunshine and pleasure.” Every morning the four boys played cricket, the two Cs, Charlie and Claude, against the two Fs, Fred and Frank in the yard outside their home. It all ended when Frank managed to break his parents’ bedroom window, and the boys were forced to find somewhere else to play. This reminded Frank of playing at The Oval years later, when he hit the ball “up and into the window of a third-floor apartment and the tenant tried to sue me.”

Frank joined the staff of Kent CCC aged 14, but only for half a day a week. His father, hoping for a well-educated son, had put him down for Tonbridge School, which later educated several generations of Cowdreys, Ed Smith and Zak Crawley among other Kent stalwarts, but before he joined, the offer came from Kent CCC. “Father wisely left the decision to me. ‘Was it school or was it cricket?’ And of course there was only one answer. At that time, and nearly forever after, nothing else seemed to matter.”

His childhood certainly shaped the man he became, but Woolley is inevitably nostalgic for the past. “My world has vanished before my eyes, and it is too late to build another.” “I must try not to shed a tear as the King of Games is beheaded – now jetted into a one-day match with different rules and regulations….. A young cricketer at Canterbury tried to put it gently – ‘Of course, Mr. Woolley, you couldn’t enjoy cricket today. It is far too scientific.’” To which Woolley’s brusque reply is that “to me it has always been very scientific. In fact I had been in cricket for ten years before I really understood it.”

I’m sure when Darren Stevens or Zak Crawley write their memoirs in their old age they will echo Frank’s somewhat disapproving words – “Inexorable change! Inevitable revolution and mutation!” but so it always goes. And even when those two are sitting in the shade of the by then enormous lime tree, Frank Woolley will still hold pride of place as Kent’s greatest ever cricketer.

0 Comments